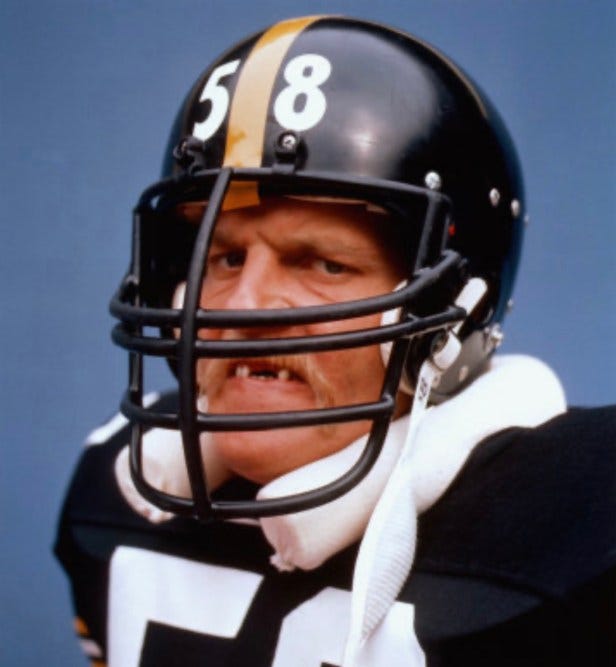

Micah's Read of the Week, Vol. 58

Honoring heroes this Labor Day, Killing Taliban fighters from an air-conditioned room, How the pandemic ends, Recipe Corner, and more.

Hello, and welcome to Micah’s Read of the Week. Happy Labor Day!

This is a newsletter filled with things Micah Wiener finds interesting.

Check out the introduction post here and the entire archive of previous newsletters here.

Please, subscribe and share with a friend.

This Labor Day, let’s honor the workers who have been on the front lines of the pandemic

This editorial from The Washington Post is perfect. Here it is in full:

“Every single day doing the same thing over and over again, and you just never think there’s going to be an end.” So commented a critical care nurse at a Florida hospital facing a surge in hospitalizations of covid-19 patients. “They are all super sick, intubated, sedated and on their bellies, it’s disheartening,” said another intensive-care nurse. “Tired, overworked and overwhelmed” was how a director of emergency medical services in Florida described hospital staff, reporting “we’re working really hard: working overtime, working late hours and taking on more than normal because we don’t have a choice.”

For 18 long, hard months, these workers have been on the front lines in the country’s fight against the coronavirus. They have been joined by people who deliver groceries, cook meals, pick up trash, patrol streets, clean hospitals and care for the frail. Despite the hardships and health risks, they do their jobs, day in and day out, too often for little pay and few benefits. As Labor Day is celebrated Monday — with the pandemic sadly far from vanquished — these essential workers should be remembered and honored above all.

It should not be lost on anyone that many of these workers won’t have the luxury enjoyed by much of the country to relax and enjoy Monday as a holiday. Instead of barbecuing with family or squeezing in a last trip to the beach, these people will be on the job, in stores and police stations and hospitals. “We don’t have a choice,” Kristy Dutton, director of emergency services at Lee Memorial and Gulf Coast Medical Center, noted in a candid post to Facebook. In return for their service, these workers increasingly are having to contend with abuse from the very people they are trying to help because of ridiculous disagreements over masking and screening protocols. Health-care professionals report being cursed, screamed at and threatened with bodily harm. Flight attendants have had to resort to taking self-defense classes to deal with misbehavior from passengers. We have all seen the videos of retail and grocery store workers having to contend with angry and irrational customers who simply refuse to follow common-sense rules about masking. It’s all unacceptable.

So, too, is the refusal of people to get vaccinations that have proved to be both effective against the coronavirus and safe. The people packing the intensive care units in Florida and elsewhere are, with few exceptions, the unvaccinated. “These people are sick, this is somebody’s mother, somebody’s sister, these people mean something,” wrote a weary Ms. Dutton. “It’s been very hard for us to understand that these people may never recover.” The best way for America to honor the selfless work of those who have been on the front lines of the pandemic is with a resolve to get the vaccinations that have proved so effective in saving lives.

I killed Taliban fighters from an air-conditioned room. Did it even help?

I became a Marine to test myself in combat. I ended up waging a remote, abstract war. Ian Cameron is a former Marine infantry officer.

Here’s a sobering and surreal look at life for American soldiers in Afghanistan. Check this lede:

For nine months in 2018 and 2019 — roughly the 18th year of America’s war in Afghanistan — I directed airstrikes against the Taliban. From an operations center made mostly of plywood in the middle of the Helmand desert in southern Afghanistan, our team of intelligence, artillery and aviation specialists deployed some of the world’s most sophisticated technology against Taliban fighters who were primarily armed with rifles designed during World War II. We tracked and hunted these militants for hours every day with multimillion-dollar, indefatigable Reaper and Predator drones. We guided A-10 Warthogs, F-18 fighter jets or Apache helicopters to these targets, and the drones’ high-powered cameras provided intimate portraits of the effect of well-aimed steel and explosives on human flesh.

I oversaw these airstrikes every day in a neat eight-hour shift — pretty much the only regular schedule I ever had in the Marines. I’d wake up in my “can,” a small but comfortable air-conditioned metal container outfitted with a bed, desk and a dresser. I would take a hot shower and shave and then walk 100 feet over to the cafeteria for a breakfast of eggs, bacon and Cheerios. Afterward, I crossed a small dusty road lined with porta johns to arrive at the operations center. I brewed a pot of coffee and then took over my shift at 8 a.m.

I killed men for the next eight hours.

The daily routine, was well, routine.

At 4 p.m. my replacement, a fellow Marine captain, would arrive. I’d brief him about what had happened that day — how many strikes we conducted, how many people we killed, how many we wounded — and where we had drones watching Taliban fighters he would kill later if he had the opportunity. (In nine months, I directed more than 250 airstrikes resulting in 304 Taliban members killed and 54 wounded.)

Once we completed our turnover checklist, I left the operations center and returned to my can. I changed into exercise clothes, hit the gym and took another hot shower. At dinner, Indian cooks served up country-fried steak or an overcooked salmon fillet with an iceberg lettuce salad, and I ate in front of a large-screen television. Later, back in my can, I called my girlfriend in the States, read a book and went to bed. I woke up the next day to do it all over again.

This is one of the new faces of war.

I knew this before my assignment; drone combat was decades old by then. Nonetheless, the sterility of this type of warfare, which allowed me to kill Taliban fighters in one moment and finish a half-eaten hamburger lunch the next, was chilling. Given the general ineffectiveness of the Afghan security forces, which were supposedly in charge of national defense at this point, it sometimes seemed less that we were supporting their efforts and more that we were engaged in a Sisyphean exercise (since the Taliban never ran out of replacement fighters).

The author shares a story about one memorable day with vivid detail. It may take your breath away.

We’d killed other guards at this exact intersection multiple times over the last three months, yet the Taliban kept ordering young men back to it again and again. (My amazement at this practice — and at the fact that fighters would dutifully return — may explain why this particular strike lingers in my mind.) After we identified a rifle sticking out from under the shawl of one of the men, we were legally cleared to kill them, but doing so would be tricky while avoiding the civilian traffic at this busy checkpoint.

We observed with a drone, but our killing machine that day was an A-10 Warthog, flying with a partner plane. As the aircraft reached the optimal point from which to drop ordnance, the tension in the operations center rose; conversations stopped, and all eyes scanned the screens for incoming traffic. We had only seconds to call out any concerns.

A dust cloud erupted on screen. Two rockets had landed at the feet of the man in the bright cap. When the dust cleared, I could see his body in the road — a dark mangle, his turban blasted off and unspooled into a black ribbon nearby. A pool of blood slowly stained the sand beneath him. The other fighter was lying in the road a few yards away. Eventually, a flatbed truck stopped, and men placed the mangled bodies on shawls to lift them into the vehicle. As the drones confirmed that it was a clean strike, meaning no civilian casualties, the tension in the control room dissipated.

And of course, no story about war is complete without horror.

But I remember feeling very differently after the strikes that did not go as smoothly — the tragic handful when we killed or maimed bystanders. I remember the dread of watching the wrong motorcycle drive into the impact zone of our bombs. I remember the gradual tightening in my stomach as a post-strike review revealed that one of the bodies on the screen was too small to be an adult.

It was in these instances that the video game stopped and the flesh-and-blood consequences of what we were doing hit me — a wave of sickness, regret and second-guessing. Yet my routine on the base would remain largely unchanged. I’d work out, grab a hot shower and listen to the Marines in the cafeteria debate the merits of competing “Bachelor” candidates over chocolate ice cream. I’d go back to my can and call my girlfriend. With a hollow feeling in my stomach, I’d stare at the aluminum roof and drift off to sleep. And then I would wake up the next day to do it all over again.

HOW THE PANDEMIC NOW ENDS

Cases of COVID-19 are rising fast. Vaccine uptake has plateaued. The pandemic will be over one day—but the way there is different now.

So where are we?

In simple terms, many people who caught the original virus didn’t pass it to anyone, but most people who catch Delta create clusters of infection. That partly explains why cases have risen so explosively. It also means that the virus will almost certainly be a permanent part of our lives, even as vaccines blunt its ability to cause death and severe disease.

The U.S. now faces a dispiriting dilemma. Last year, many people were content to buy time for vaccines to be developed and deployed. But vaccines are now here, uptake has plateaued, and the first surge of the vaccine era is ongoing. What, now, is the point of masking, distancing, and other precautions?

The answer, as before, is to buy time—for protecting hospitals, keeping schools open, reaching unvaccinated people, and more. Most people will meet the virus eventually; we want to ensure that as many people as possible do so with two doses of vaccine in them, and that everyone else does so over as much time as possible. The pandemic isn’t over, but it will be: The goal is still to reach the endgame with as little damage, death, and disability as possible.

If you needed more evidence that vaccines work, here are some facts:

The measures that stymied the original coronavirus still work against its souped-up variant; vaccines, in particular, mean that half of Americans are heavily protected in a way they weren’t nine months ago. Full vaccination (with the mRNA vaccines, at least) is about 88 percent effective at preventing symptomatic disease caused by Delta. Breakthrough infections are possible but affect only 0.01 to 0.29 percent of fully vaccinated people, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Breakthroughs might seem common—0.29 percent of 166 million fully vaccinated Americans still means almost 500,000 breakthroughs—but they are relatively rare. And though they might feel miserable, they are much milder than equivalent infections in unvaccinated people: Full vaccination is 96 percent effective at preventing hospitalizations from Delta, and unvaccinated people make up more than 95 percent of COVID-19 patients in American hospital beds. The vaccines are working, and working well. Vaccinated people are indisputably safer than unvaccinated people.

Delta is bad.

Delta’s extreme transmissibility negates some of the community-level protection that vaccines offer. If no other precautions are taken, Delta can spread through a half-vaccinated country more quickly than the original virus could in a completely unvaccinated country. It can even cause outbreaks in places with 90 percent vaccination rates but no other defenses. But the math means that “there’s not really a way to solve the Delta problem through vaccination alone,” Murray said.

But then what?

Herd immunity—the point where enough people are immune that outbreaks automatically fizzle out—likely cannot be reached through vaccination alone. Even at the low end of the CDC’s estimated range for Delta’s R0, achieving herd immunity would require vaccinating more than 90 percent of people, which is highly implausible. At the high end, herd immunity is mathematically impossible with the vaccines we have now.

This means that the “zero COVID” dream of fully stamping out the virus is a fantasy. Instead, the pandemic ends when almost everyone has immunity, preferably because they were vaccinated or alternatively because they were infected and survived.

The bottom line?

Think of it this way: SARS-CoV-2, the virus, causes COVID-19, the disease—and it doesn’t have to. Vaccination can disconnect the two. Vaccinated people will eventually inhale the virus but need not become severely ill as a result. Some will have nasty symptoms but recover. Many will be blissfully unaware of their encounters. “There will be a time in the future when life is like it was two years ago: You run up to someone, give them a hug, get an infection, go through half a box of tissues, and move on with your life,” Lavine said. “That’s where we’re headed, but we’re not there yet.”

Podcast Promotion of the Week

Big week for podcasts. Some might even say it’s podcast week.

First, with the return of football season, Back Door Cover is can’t miss. Brad Kee and I break down the eventful week 1 of the college football season.

On Mind of Micah, I am joined by John Duda. He was recently hit by a car. We talk about that and restaurants. You’ll enjoy it.

Recipe Corner

We’re getting dangerously close to the end of the Summer of Skirt steak. And you know we’re pairing today’s grilled meat with not one, but two cooling, seasonal salads.

Chipotle Honey-Marinated Steak

2 tablespoons fresh lime juice (from 1 lime)

1/2 large yellow onion, cut into 1/4-inch dice

1 tablespoon plus 1 1/2 teaspoons minced garlic

3 canned chipotle chiles, chopped

2 tablespoons chipotle-infused honey (see headnote), plus more for serving

2 teaspoons ground cumin

2 teaspoons kosher salt

1 teaspoon ancho chile powder

1 teaspoon Spanish smoked paprika

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 1/2 pounds skirt steak

Combine the lime juice, onion, garlic, chipotle chiles, honey, cumin, salt, ancho chili powder, smoked paprika and oil in a resealable container. Add the steak and seal, pressing out as much air as possible. Let it sit at room temperature for 1 hour, or refrigerate for up to 24 hours.

Prepare the grill for direct heat: If using a gas grill, preheat to medium-high (375 to 400 degrees) with the lid closed. If using a charcoal grill, light the charcoal or wood briquettes; when the briquettes are white hot and covered with ash, distribute them evenly over the cooking area. For a medium-hot fire, you should be able to hold your hand about 6 inches above the coals for 4 to 6 seconds. Have ready a spray water bottle for taming any flames. Brush the grill grate with oil, if desired.

Remove the steak from the marinade and wipe off any excess marinade; discard the marinade. Grill or broil the steak for 6 to 7 minutes on each side (for medium-rare).

Transfer the meat to a cutting board and let it rest for 10 minutes, then cut it on the diagonal, against the grain, into 1/2-inch-thick slices. Drizzle with more hot honey, if desired. Serve right away.

Watermelon and Cucumber Salad With Ginger, Lime and Mint

1 1/4 pounds diced watermelon (about 4 cups)

1 medium English cucumber, trimmed, quartered lengthwise and cut into 1/2-inch thick pieces (about 3 cups)

2 tablespoons fresh lime juice

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

2 teaspoons finely grated fresh ginger

1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt or table salt

1/4 cup fresh mint leaves, torn

In a large bowl, toss the watermelon and cucumber until combined.

In a small bowl, whisk together the lime juice, olive oil, ginger and salt until combined. Drizzle the dressing over the watermelon and cucumber and gently toss to coat, then add the mint. Gently toss to combine and serve.

Fresh Summer Peach Salad

1 Thai chile pepper, minced (seeded if desired)

1 clove garlic, minced

1/4 cup fresh lime juice (from 2 limes)

2 tablespoons fish sauce

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 tablespoon light brown sugar

1 medium shallot, thinly sliced (about 1/4 cup)

1 pound peeled seedless watermelon, cut into 1/4-inch-thick matchsticks (about 3 cups)

Flesh of 1 ripe mango, cut into 1/4-inch-thick matchsticks (about 1 cup)

2 medium peaches, pitted and cut into 1/4-inch-thick matchsticks or thin wedges (about 2 cups)

1 medium cucumber, peeled, seeded and cut into 1/4-inch-thick matchsticks (about 1 1/4 cups)

1/2 cup fresh Thai basil leaves

1/2 cup fresh mint leaves

1/2 cup chopped, dry-roasted unsalted peanuts, for garnish

Whisk together the chile pepper, garlic, lime juice, fish sauce, oil, brown sugar and shallot in a large mixing bowl until combined. Reserve 1/2 cup of the vinaigrette separately.

Add the watermelon, mango, peaches, cucumber, Thai basil and mint to the bowl with most of the dressing; gently toss to coat. Scatter the peanuts over the surface of the salad and serve right away along with the reserved dressing.

Where else can I find Micah content?

Podcasts: Mind of Micah, Back Door Cover, Too Much Dip

Twitter: @micahwiener & @producermicah (Why two twitters? It’s a long story)

Instagram: @micahwiener

LinkedIn: @micahwiener

Peloton: #badboysofpelly@micahwiener

Dispo: @micahwiener

Email: micahwiener@me.com

NMLS #2090158